Introduction

The human body can use carbohydrate, fat, or protein to generate energy, only carbohydrate and fat are major fuel sources. Protein’s role in the diet is mainly to provide amino acids needed by the body to make its own proteins, for structure and function.

How the Body Generates Energy

During digestion, carbohydrates, fats, and proteins from food are broken down into their basic components — carbohydrates are broken down into simple sugar and turned into glucose, proteins are broken down into amino acids, and fat is broken down into fatty acids and glycerol.

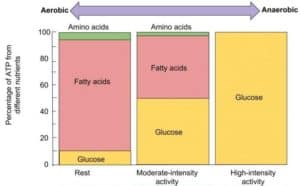

Protein is not usually used for energy, although small amounts of amino acids from broken-down protein are used by the body when we’re resting, and even smaller amounts are used when we’re doing moderate-intensity exercise [1]. During moderate-intensity exercise, our body will use half fatty acids as fuel and half glucose. During high-intensity exercise, our body will rely on glucose as fuel — both from the carbohydrates we eat, as well as generated by breaking down fat stores. It is only if we are not getting enough calories in our food or from our fat stores that protein will be used for energy [2] and burned as fuel. If more protein is eaten than is needed by the body, the excess will be broken down and stored as fat [2].

Determining Individual Macros

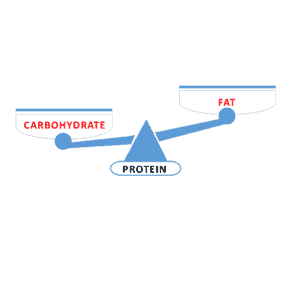

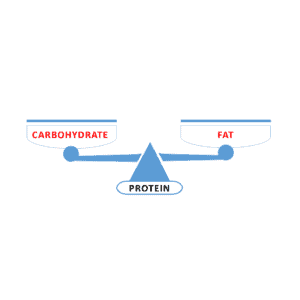

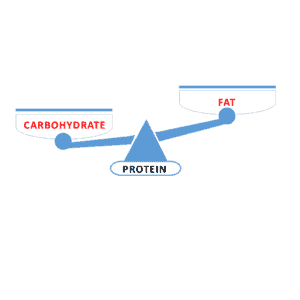

In determining the amount of protein, fat, and carbohydrate that each needs (i.e., “macros”), choosing the amount of protein we require comes first. The amount of carbohydrate and fat is chosen after that — based on the needs of the individual for blood sugar control and their metabolic health. Since it is not a primary fuel source for the body, think of protein as the base of a balance scale — providing the body with building blocks for structure and function. The two arms of the balance are the two sources of fuel for energy: carbohydrate and fat.

We need to have enough protein for our needs, but not so much as to either store the excess as fat — or worse, to exceed the ability of our body to get rid of the excess nitrogen-by-product in the urine. Since 84% of the nitrogen waste produced from protein intake is excreted as urea in the urine [3], the safe upper limit of protein intake is based on the maximum rate of urea production, which is 3.2 g protein per kg of lean body mass [4].

NOTE: This calculation is based on lean body mass (also known as Ideal Body Weight or IBW), not total body weight. Lean body mass can be assessed using a DEXA scan or estimated by using relative fat mass (RFM). The amount of fat someone has can be estimated from total body weight, minus their estimated RFM, as described in this article.

The RDA for healthy adults is calculated at 0.8 g protein/kg of IBW [5]. For those who are physically active, the American College of Sports Medicine [6] recommends a protein intake of 1.2—2.0 g protein/kg IBW per day. Older people also need more protein to prevent sarcopenia (muscle loss), with intake between 1.0 and 1.5 g protein/kg IBW per day best meeting needs during aging [7], [8].

Balancing Carbohydrate and Fat as Fuel

There are 3 ways that carbohydrate and fat as fuel can be balanced — and which one is best for a specific individual depends on their protein needs, as well as their metabolic health.

Higher Carbohydrate than Fat

The standard diet recommended by national dietary guidelines aims for the majority of fuel (energy intake) to come from carbohydrates. These are HCLF (High Carb, Low Fat) diets, providing 45-65% of total energy intake. For those who are insulin resistant or have type 2 diabetes, reducing overall carbohydrate intake has demonstrated the most evidence for improving glycemia [11]. Be sure to read the following post on how specific fiber types impact insulin response.

Higher Fat than Carbohydrate

Low Carb, High Fat (LCHF) diets range from “keto” patterns providing ~75% fat to approaches recommending 60-70% fat and 20-30% protein [12]. These are defined clinically as very low carbohydrate (20—50g/day) or low carbohydrate (<130g/day) [13], [14].

Balanced Fat and Carbs

s type of diet is a High Protein, Low Fat (HPLF) diet, such as the P:E Diet, which recommends 40% protein with equal amounts of fat (30%) and carbohydrate (30%) [9].

Low Carb High Protein

Low Carb High Protein (LCHP) diet provides ~25-30% protein, offering more satiety at less than half the calories of fat [15]. This meal pattern is ideal for fat loss while preserving muscle mass.

Final Thoughts…

Meal patterns always come down to a choice between “low carb” or “low fat”. For those seeking to put type 2 diabetes into remission, low carb options are often the most effective because having adequate protein with healthy fats keeps people from overeating.

Nutrition is BetterByDesign!

More Info?

Learn about me and the support I can provide for obtaining and maintaining a healthy body weight, as well as normalizing high blood sugar and cholesterol.. View my Comprehensive Dietary Package.

To your good health!

Joy

You can follow me on:

Twitter: https://twitter.com/jyerdile

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/BetterByDesignNutrition/

References

- LibreTexts Medicine. Zimmerman M, Snow B. An Introduction to Nutrition: 16.4 Fuel Sources. 2020. [https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Nutrition/Human_Nutrition_2020e_(Hawaii)/16%3A_Performance_Nutrition/16.04%3A_Fuel_Sources]

- Youdim A. Merck Manual Professional Version: Carbohydrates, Proteins, and Fats. 2021. [https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/nutrition-general-considerations/carbohydrates-proteins-and-fats]

- Tomé D, Bos C. Dietary Protein and Nitrogen Utilization. The Journal of Nutrition. 2000;130(7):1868S–1873S. doi:10.1093/jn/130.7.1868S [https://academic.oup.com/jn/article/130/7/1868S/4686302]

- Rudman D, DiFulco TJ, Galambos JT, et al. Maximal rates of excretion and synthesis of urea in normal and cirrhotic subjects. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1973;52(9):2241-2249. doi:10.1172/JCI107410 [https://www.jci.org/articles/view/107410]

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2005. doi:10.17226/10490 [https://www.nap.edu/read/10490/chapter/1]

- Thomas DT, Erdman KA, Burke LM. American College of Sports Medicine Joint Position Statement: Nutrition and Athletic Performance. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2016;48(3):543-568. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000000852 [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26891166/]

- Fielding RA, Vellas B, Evans WJ, et al. Sarcopenia: an undiagnosed condition in older adults. Current consensus definition: prevalence, etiology, and consequences. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2011;12(4):249-256. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2011.01.003 [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21527165/]

- Bauer J, Biolo G, Cederholm T, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for optimal dietary protein intake in older people: a position paper from the PROT-AGE Study Group. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2013;14(8):542-559. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2013.05.021 [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23867520/]

- Institute of Medicine. Front-of-Package Nutrition Rating Systems and Symbols: Phase I Report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2010. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK209847/]

- Araújo J, Cai J, Stevens J. Prevalence of Optimal Metabolic Health in American Adults: NHANES 2009–2016. Metabolic Syndrome and Related Disorders. 2019;17(1):46-52. doi:10.1089/met.2018.0105 [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30484738/]

- Evert AB, Dennison M, Gardner CD, et al. Nutrition Therapy for Adults With Diabetes or Prediabetes: A Consensus Report. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(5):731-754. doi:10.2337/dci19-0014 [https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/42/5/731/40480/Nutrition-Therapy-for-Adults-With-Diabetes-or]

- Volek JS, Phinney SD. The Art and Science of Low Carbohydrate Living. Beyond Obesity; 2011. [https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/mX_vXwAACAAJ]

- Feinman RD, Pogozelski WK, Astrup A, et al. Dietary carbohydrate restriction as the first approach in diabetes management: Critical review and evidence base. Nutrition. 2015;31(1):1-13. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2014.06.011 [https://www.nutritionjrnl.com/article/S0899-9007(14)00332-3/fulltext]

- Diabetes Canada. Position Statement on Low Carbohydrate Diets for Adults with Diabetes: A Rapid Review. Canadian Journal of Diabetes. 2020;44(4):295-299. doi:10.1016/j.jcjd.2020.04.001 [https://www.canadianjournalofdiabetes.com/article/S1499-2671(20)30113-1/fulltext]

- Stubbs J, Ferres S, Horgan G. Energy Density of Foods: Effects on Energy Intake. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2000;40(6):481-515. doi:10.1080/10408690091189248 [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11186237/]

© 2025 BetterByDesign Nutrition Ltd.

Joy is a Registered Dietitian Nutritionist and owner of BetterByDesign Nutrition Ltd. She has a postgraduate degree in Human Nutrition, is a published mental health nutrition researcher, and has been supporting clients’ needs since 2008. Joy is licensed in BC, Alberta, and Ontario, and her areas of expertise range from routine health, chronic disease management, and digestive health to therapeutic diets. Joy is passionate about helping people feel better and believes that Nutrition is BetterByDesign©.