INTRODUCTION: To avoid ignoring important warning signs that our body is not working as it should, we first need to understand how it is supposed to work and what begins to go wrong — long before we receive a diagnosis of Type 2 Diabetes. That way we can make the necessary dietary and lifestyle changes to prevent it from ever progressing further. Type 2 Diabetes can be prevented and this article explains what to look for.

When the human body is healthy, it maintains blood sugar between 3.3-5.5 mmol/L (60-100 mg/dl). The beta (β) cells of the pancreas produce the hormone insulin, store it and release it into the blood in the correct amount and at the right time. The β-cells of healthy people are constantly making insulin and storing most of it within the cell until it receives a signal that food with carbohydrate has been eaten. β-cells constantly release a little bit of insulin all the time in very small pulses called basal insulin. This basal insulin allows the body to use blood sugar even when the person hasn’t eaten for several hours or even longer.

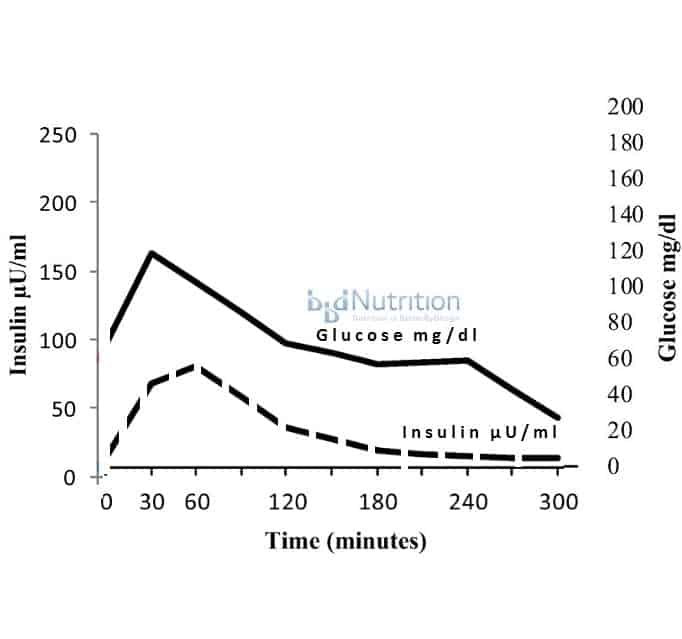

The rest of the insulin stored in β-cells is only released when blood sugar rises after the person eats foods containing carbohydrate. This insulin is released in two phases [1]. The first-phase insulin response occurs as soon as the person begins to eat and peaks within 30 minutes and can be seen at 30 minutes on the graph above.

The amount of the first-phase insulin release is based on how much insulin the body is used to needing each time the person eats. Provided the person eats more or less the same amount of carbohydrate-based food at each meal, the amount of insulin in the first-phase insulin response will be enough to move the excess glucose from the food into the cells, returning blood sugar to ~5.5 mmol/L (100 mg/dl). If there is not enough insulin in the first-phase insulin response, the β-cells will release a smaller amount of insulin within an hour to an hour and a half of the person beginning to eat. This is the second-phase insulin response [1] and can be seen at 60 minutes on the graph above.

In healthy people, the combination of the larger first-phase insulin response and the smaller second-phase insulin response is sufficient to keep blood sugar level from rising above 7.8 mmol/L (140 mg/dl), even after the person has eaten a lot of carbohydrate. In healthy people whose β-cells are working properly and receiving the correct signals from their small intestines, blood sugar levels will return to their normal fasting level between 4.6-5.5 mmol/L (83-100 mg/dl range) by 2 hours.

Dysfunctional Insulin Release & Insulin Resistance

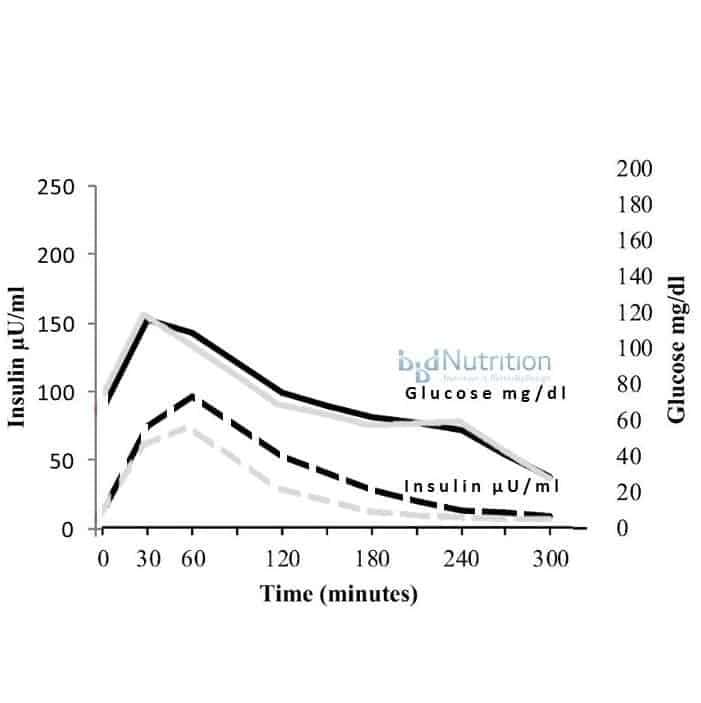

In the early stages when people are becoming insulin resistant, receptors in the liver and muscle cells begin to stop responding properly to insulin’s signal. To compensate, the β-cells of the pancreas begin producing and releasing more insulin (hyperinsulinemia). This can be seen on the graph below (in black), which is superimposed over the normal glucose and insulin curve (light grey).

As a result of the insulin resistance of the liver and muscle cells, it takes more insulin to move the same amount of glucose into the cells.

At this point, only 3% of people will meet the criteria for diagnosis with Type 2 Diabetes [2].

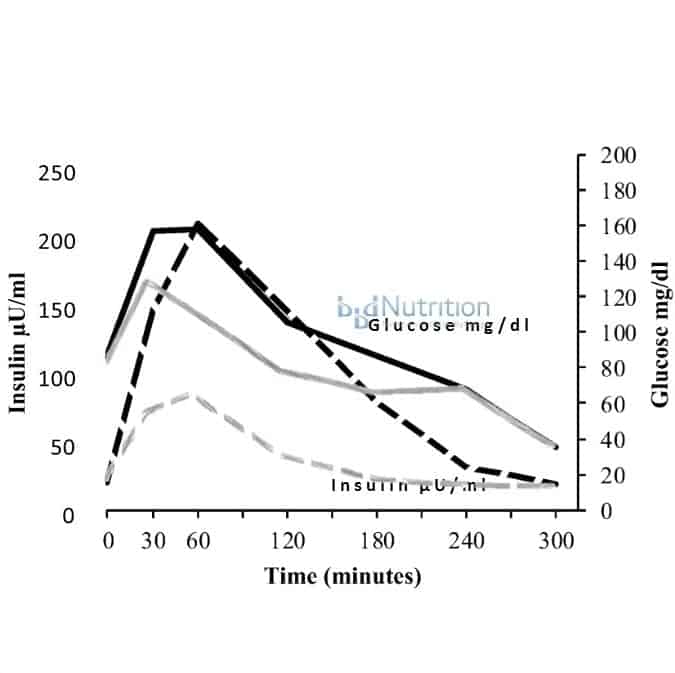

Insulin resistance doesn’t come by itself but is accompanied by hyperinsulinemia — too much insulin in the blood. Hyperinsulinemia is the result of the body trying to compensate for insulin resistance by making more and more insulin to try to keep blood sugar levels normal. With ongoing high intake of carbohydrate, especially refined carbohydrate the amount of insulin that has to be released from the β-cells is enormous (see the dashed black line on the graph below compared to the dashed grey line of a healthy person).

The first-phase insulin response won’t produce enough insulin be able to clear the extra blood glucose after a high carbohydrate meal into the cells and even the second-phase insulin response won’t be enough to overcome the insulin resistance of the cells. At this point, the β-cells of the pancreas are unable to make enough insulin to clear the excess glucose from the blood and blood glucose rises above the normal high peak of 7.8 mmol/L (140 mg/dl), to levels of 9.0 mmol/L (160 mg/dl) or higher.

In this case, since blood glucose is able to be returned to baseline after 2 hours, only 7% of people will be diagnosed with Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) but clearly these people’s insulin response and blood glucose response (in black) is very dysfunctional compared to that of a healthy person (in grey). In fact, almost 30% of people will have normal blood glucose, but they already have hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance.

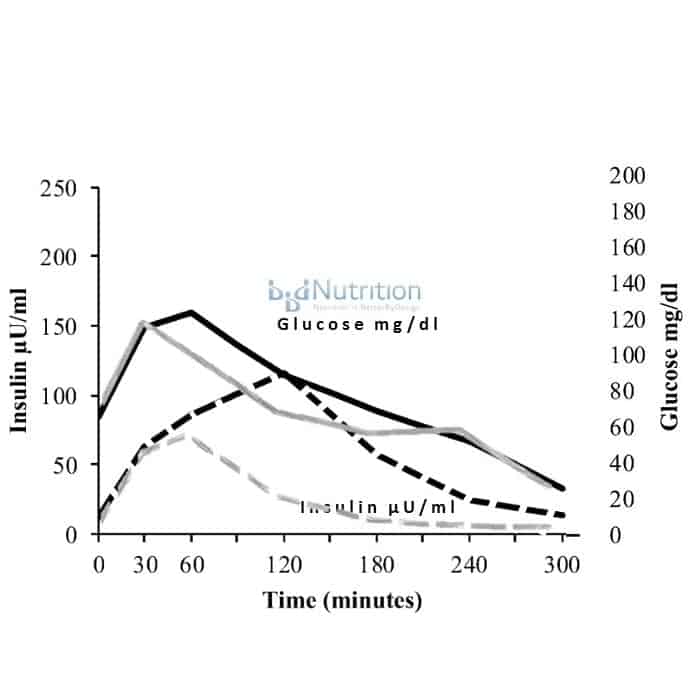

If the body is forced to continue to process a high refined-carbohydrate diet, it will make more and more insulin but not without a cost to the β-cells of the pancreas. β-cell failure will begin to occur as a result of this high demand [3].

Since most physicians only monitor fasting blood glucose (FBG) to detect whether their patients are becoming insulin resistant or Diabetic, they and their patients have no idea that between ½ and 1 hour after beginning a meal, the person’s blood sugar had reached levels well in excess of the normal high peak of 140 mg/dl (7.8 mmol/L). Blood sugar in these individuals often goes as high as 9.0 mmol/L (160 mg/dl ) and even higher but no one knows because no one is checking for it.

A standard fasting blood glucose test won’t pick this up and even if a doctor requisitions a two-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) where the person is required to fast and then drink a standard amount of glucose and have their blood sugar checked, glucose levels are only measured at baseline when the person is fasting (FBG) and after 2 hours, by which time blood sugar has returned to normal, so this huge peak in blood sugar won’t be seen.

People with these abnormal insulin-glucose responses are at significantly increased risk for developing Type 2 Diabetes and the cardiovascular disease (heart attack and stroke) that often accompanies it, but if no one checks, no one knows.

We can only obtain the right answers if we ask the right question, but often we are asking the wrong questions.

By the time people’s insulin and glucose curves look like above in black, ~75% of people will already meet the diagnostic criteria Type 2 Diabetes [2].

When people’s fasting blood sugar and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C) falls in the normal range, it can’t simply be assumed that “everything’s fine” if these same individuals also have other symptoms that are known to be associated with hyperinsulinemia, including high blood pressure (hypertension), high triglycerides (TG) and/or low HDL cholesterol [4]. If fasting blood glucose and/or HbA1C lab test results comes back within normal range and the person has some of these other symptoms and/or a family history of them, then requisitioning a fasting insulin test along with a fasting blood glucose test will enable some calculations to be done to estimate insulin resistance using the homeostasis model assessment (HOMA-IR) described in previous articles, but assessing hyperinsulinemia is a more involved process as it requires assessing both insulin response and glucose response simultaneously over several hours. The problem is that hyperinsulinemia is mechanistically linked to Metabolic Syndrome (described below), Type 2 Diabetes and as a result, cardiovascular disease (atherosclerosis, thrombosis) and other diseases associated with Metabolic Syndrome. Hyperinsulinemia is also an independent risk factor for specific cancers (including breast and colon/rectum, Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia and non-alcoholic liver disease [3]. Hyperinsulinemia is a silent disease, with no overt symptoms. Clinical tools such as assessing insulin and glucose at the same time in response to a glucose load (called a ‘Kraft Assay’) may be useful to predict those who are at risk. In order to be able to prevent people from receiving this diagnosis, clinicians must ask the right questions.

If a doctor is willing to requisition a 2-hour glucose tolerance test, then something as simple as having blood glucose checked at baseline, 1/2 an hour, 1 hour and 2 hours — and not just at baseline and at 2 hours will “catch” abnormal spikes after a carbohydrate load. While it is not as involved as a Kraft Assay which assesses insulin levels simultaneously with glucose levels over several hours, it can provide some useful information. Such a simple addition is not very expensive and can go a very long way to enabling a person to make dietary and lifestyle changes to reverse hyperinsulinemia and as a result, decrease insulin resistance and avoid a diagnosis of Type 2 Diabetes. Certainly, left on its own, there is a good chance these individuals will be diagnosed even though their blood sugar didn’t reflect the risk far enough in advance.

Someone taking their own blood sugar reading at 1/2 hour and an hour after eating a high carbohydrate meal can provide them with sufficient early warning to look further. I have loaned glucometers to my clients for just this purpose. It doesn’t need to be complicated. We simply need to ask the right questions.

If people already have some form of cardiovascular disease (CVD), essential hypertension (high blood pressure that has no identifiable cause), Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS) or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) we need to consider that insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia are very often associated [4].

We need to look past what appears on the surface to be ‘normal’, because we may be overlooking early warning signs because we didn’t ask the right questions.

More Info

If you would like more information, you can learn about me here.

To your good health!

Joy

You can follow me on:

Twitter: https://twitter.com/jyerdile

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/BetterByDesignNutrition/

Copyright ©2018 BetterByDesign Nutrition Ltd.

LEGAL NOTICE: The contents of this blog, including text, images and cited statistics as well as all other material contained here (the ”content”) are for information purposes only. The content is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice, medical diagnosis and/or treatment and is not suitable for self-administration without the knowledge of your physician and regular monitoring by your physician. Do not disregard medical advice and always consult your physician with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or before implementing anything you have read or heard in our content.

References

- Del Prato, S., P. Marchetti, and R.C. Bonadonna, Phasic insulin release and metabolic regulation in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes, 2002. 51 Suppl 1: p. S109-16.

- Crofts, C., et al., Identifying hyperinsulinaemia in the absence of impaired glucose tolerance: An examination of the Kraft database. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 2016. 118: p. 50-7.

- Crofts, C., Understanding and Diagnosing Hyperinsulinemia. 2015, AUT University: Auckland, New Zealand. p. 205.

- Halban, P.A., et al., β-cell failure in type 2 diabetes: postulated mechanisms and prospects for prevention and treatment. Diabetes Care, 2014. 37(6): p. 1751-8.

- Reaven, G., The metabolic syndrome or the insulin resistance syndrome? Different names, different concepts, and different goals. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am, 2004. 33(2): p. 283-303.

Joy is a Registered Dietitian Nutritionist and owner of BetterByDesign Nutrition Ltd. She has a postgraduate degree in Human Nutrition, is a published mental health nutrition researcher, and has been supporting clients’ needs since 2008. Joy is licensed in BC, Alberta, and Ontario, and her areas of expertise range from routine health, chronic disease management, and digestive health to therapeutic diets. Joy is passionate about helping people feel better and believes that Nutrition is BetterByDesign©.